Bum Bags and Fanny Packs (Part 3); How USA and Australian cultural differences play out within organisations

Part 3 of 3

How Differences Reveal Themselves

In Part 1, we looked at the big contextual picture which shapes US and Australian national cultures and permeates organisations that call these countries home. In Part 2 we discussed how cultural variance reveals itself through humour, leadership, work balance and wellbeing. In Part 3 we take a look at cultural differentiators in relation to faith, national pride and guns. This final part also includes key learnings.

The aims of this three-part article are to:

- share insights from our lived experience of adapting to cultural differences and working with our global clients

- stimulate considered and respectful dialogue around cultural differences that, if not acknowledged, have the potential to create misunderstanding and impede individual and organisational development

- help organisations learn, adapt, reap the benefits of diversity and build global growth capability

Before we embark on Part 3 of this exploration of modern cross-cultural contrasts we want to acknowledge the indigenous cultures that existed in what are now the USA and Australia, long before colonial influence shaped both countries, and which continue to proudly exist today.

Faith

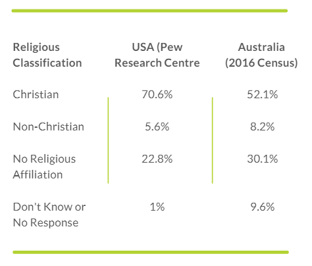

In both the USA and Australia, the number of people claiming no religious affiliation is increasing. Current data from the Pew Research Centre indicates that nearly 23% of Americans now claim no religion. In the latest Australian Census (2016), around one third of Australians categorised themselves as having no religion, up 88% since the 2006 Census.

More than 70% in the US, and just over 50% in Australia, affiliate with a Christian faith. The percentage of non-Christian believers in Australia is slightly higher than in the US.

Australia is more secular than the USA and the American story cannot be told without telling the story of religion. The persecution of Puritans in England drove them to the New World. So it was with Quakers, Baptists, Shakers, Jews, and other religious minorities, all of whom viewed America as a place they would be free to practice their faith.

Australia is more secular than the USA and the American story cannot be told without telling the story of religion. The persecution of Puritans in England drove them to the New World. So it was with Quakers, Baptists, Shakers, Jews, and other religious minorities, all of whom viewed America as a place they would be free to practice their faith.

Religion, particularly the Judeo-Christian variety, permeates American culture and its institutions in a way not experienced in Australia. Midwest and Southern American states have significantly higher proportions of the population affiliated to the Christian faith than West and North Eastern states. For example, only 58% of those living in Massachusetts are Christian while 86% of Alabamians claim Christian affiliation. This is in contrast to Australia, where the proportion of the population affiliated to Christianity varies much less from state to state.

So, where a person comes from within the US and where an organisation is based, can result in very different views and depth of religious belief.

Another notable difference between the two nations is the levels of public and private advocation of the majority religions. For the most part, Christians in the US feel freer to openly express their religion and evangelise. In Australia, most tend to view religion as a more personal, private affair. Australians have a low-temperature expectation of religion. With exceptions such as Hillsong Church, overt proselytising is often viewed with suspicion.

Australia’s current Prime Minister is a deeply religious person, but not even he will risk god blessing Australia. Across the Pacific, ever since 1973 when Richard Nixon first publicly used the phrase to try and control damage from the Watergate scandal, convention dictates that incumbent and aspiring US Presidents end their addresses with “God bless the United States of America”.

National Pride

National pride and patriotism also play out in somewhat different ways in both countries. Unlike Europe, which has been managing cross-cultural borders (sometimes very badly) for thousands of years, the US is more insular and culturally isolated. Australia can also suffer from cultural insularity but, partially due to global cultural visibility being relatively low compared to the US, the implications are usually not so obvious.

National pride and patriotism also play out in somewhat different ways in both countries. Unlike Europe, which has been managing cross-cultural borders (sometimes very badly) for thousands of years, the US is more insular and culturally isolated. Australia can also suffer from cultural insularity but, partially due to global cultural visibility being relatively low compared to the US, the implications are usually not so obvious.

In Australia, the forceful voices from radio shock jocks are countered by coverage via broadcasters like the Special Broadcasting Service (SBS) and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). While the US has its Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) and National Public Radio (NPR), they do not have the same reach as their Australian counterparts which, when added, consistently make up around 24% of overnight TV viewing (Black Box, 2020). When you combine the less nuanced coverage of domestic and world affairs with America’s military might and ebbing global sway, the result can be a particularly fervent style of hand-on-heart patriotism. Australians are patriotic too, but it is usually tempered by a scepticism about excessive flag-waving.

From an insider American perspective, the potential sources of pride are numerous. It was an American who first set foot on the moon, the US is home to more than 30 Nobel Prize winners, it’s where the internet was invented and, it was American intervention during WWII that enabled Allied Forces to defeat Nazi Germany.

Historically, emotional rallies designed to stir nationalistic pride were needed to unite diverse groups into a single force, capable of taking on the English military. Group psychology, which was initially cultivated along racial, religious, civic or state lines, has, over time, been partially transferred to the national level.

The story of America, which advocates membership of Team USA and inspires strong patriotism, is a vitally important mechanism for holding the nation together and keeping the states united. However, as we have seen in recent years, the same patriotism that can unite Americans, can also divide them.

By contrast, strong nationalism can carry negative connotations for many Australians. Perhaps this is a legacy of 19th century British discouragement of Australian patriotism, or the result of having no narrative around revolutionary glory, evident in other modern nations that have fought their way into existence, like France, Ireland and the USA.

By contrast, strong nationalism can carry negative connotations for many Australians. Perhaps this is a legacy of 19th century British discouragement of Australian patriotism, or the result of having no narrative around revolutionary glory, evident in other modern nations that have fought their way into existence, like France, Ireland and the USA.

Within US organisations and in society more broadly, there is an especially high pedestal reserved for military men and women who have served the country in uniform. There are a few days in the Australian calendar, most notably ANZAC Day, when all things military take centre stage. But once the fanfare of these events has passed, military people recede into society to take their place alongside their fellow citizens, with little in the way of special treatment. Despite the occasional zealous pleas of an Australian politician to adopt a more reverent approach, usually after returning from a fact-finding tour of the USA, neither the general public nor service men and women have much of an appetite for adopting American ways on this matter.

Guns

Which brings us to guns. For most Australians, US cultural addiction to firearm ownership is perplexing. Even progressive thinking citizens in America can have strong views on the constitutional right to bear arms, albeit with a few more checks and balances in place.

The Second Amendment to the American Bill of Rights reads, “A well-regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.”

This single sentence, aimed at enabling citizens to protect themselves against a rogue domestic government, means the right to bear arms is ingrained in US social psyche in a way that is inconceivable to the majority of Australians. Maybe today, with so many guns in circulation, there is some rationale for everyone being armed to the teeth. But it is a thoroughly alien concept to most outside the USA.

It is certainly hard to imagine the US purging guns in the same way Australia did after the Port Arthur massacre. This cultural difference may also be tied to the individual vs collective balance. For many, the individual right to defend oneself appears simply to outweigh the collective consequences of having so many firearms in circulation.

Australians are prone to naively launching into a debate about gun control with US colleagues. Often around the bottom of the second bottle of Shiraz and after they’ve chuckled their way through the double entendre of Bum Bags and Fanny Packs. But, where guns are concerned, humour can quickly evaporate to lay bare a cultural chasm that no amount of light-heartedness or logic can bridge. This particular topic, perhaps like no other, reminds us that we have been shaped in similar moulds (or molds) but not the same one.

Learnings:

- Cultural stereotyping is really not helpful, inside or outside organisations, but seeking to understand cultural nuance and listening to how things are perceived through different cultural lenses is important for any globally aspiring organisation.

- If you want to understand cultural differences in organisations around the world, it pays to build some knowledge of the history and national cultures in which they operate.

- National cultures strongly permeate organisations and, unless acknowledged and openly discussed, unconscious cultural bias can lead to blind spots and misunderstandings which make it more difficult for organisations to achieve cross-cultural success.

- Leaders should focus on respecting, harnessing, and learning to live with cultural diversity rather than seeking unattainable cultural homogeneity within their organisations.

- Sometimes you really do need to agree to disagree and that’s just fine as long as it is done with respect and an emphasis on maintaining high quality, trusting working relationships.